Functional Measures for Fall Risk in the Acute Care Setting a Review

- Research Article

- Open Access

- Published:

Autumn adventure every bit a function of time after admission to sub-acute geriatric hospital units

BMC Elderliness book 16, Article number:173 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

At that place is evidence about fourth dimension-dependent fracture rates in different settings and situations. Lacking are data about underlying time-dependent fall risk patterns. The objective of the study was to analyse fall rates as a function of time afterwards admission to sub-acute infirmary units and to evaluate the fourth dimension-dependent bear on of clinical factors at baseline on fall risk.

Methods

This retrospective cohort written report used data of five,255 patients admitted to sub-acute units in a geriatric rehabilitation clinic in Germany between 2010 and 2014. Falls, personal characteristics and functional condition at admission were extracted from the hospital data system. The rehabilitation stay was divided in iii-day time-intervals. The fall rate was calculated for each time-interval in all patients combined and in subgroups of patients. To analyse the influence of covariates on fall risk over fourth dimension multivariate negative binomial regression models were applied for each of five fourth dimension-intervals.

Results

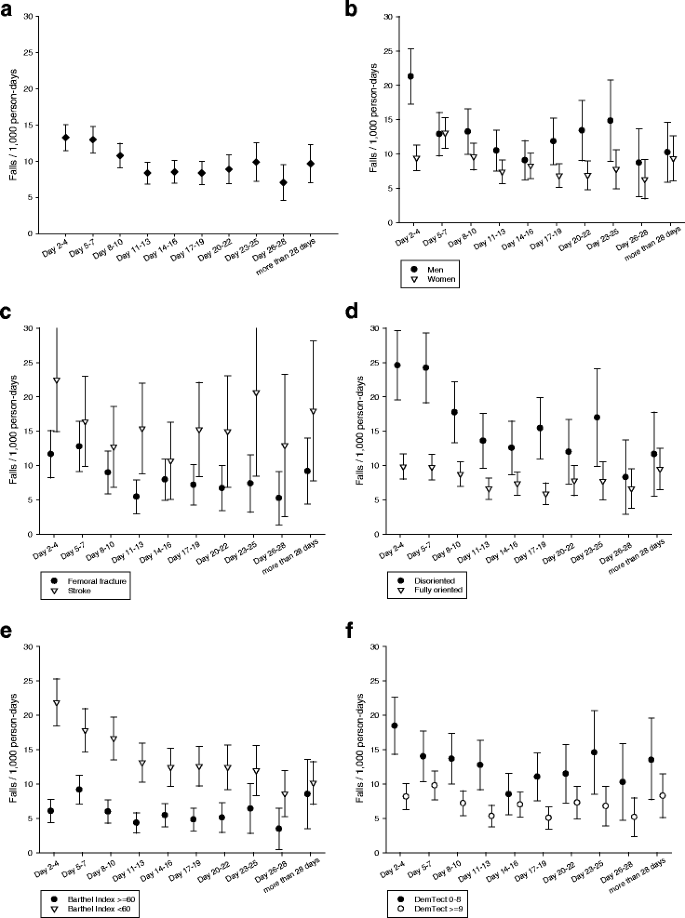

The overall autumn rate was 10.2 falls/one,000 person-days with highest fall risks during the get-go calendar week and decreasing risks within the following weeks. A particularly pronounced gamble pattern with loftier fall risks during the beginning days and decreasing risks thereafter was observed in men, disoriented people, and people with a low functional condition or impaired cognition. In disoriented patients, for example, the fall charge per unit decreased from 24.6 falls/ane,000 person-days in day 2–4 to near thirteen falls/1,000 person-days 2 weeks later. The incidence rate ratio of baseline characteristics changed also over fourth dimension.

Conclusions

Fall risk differs considerably over time during sub-acute hospitalisation. The strongest clan between time and autumn adventure was observed in functionally limited patients with high risks during the showtime days later admission and declining risks thereafter. This should be considered in the planning and awarding of autumn prevention measures.

Background

It seems obvious that individual autumn risks could change within brusk time periods. Therefore, information technology is remarkable that in that location are no studies which analysed fall rates as a function of fourth dimension in a systematic way. In fracture epidemiology there is some evidence about time-dependent risks. Two previous studies, for instance, demonstrated that the beginning time after admission to a nursing habitation is a high-risk situation for fragility fractures [i, two]. In these studies the fracture run a risk after admission was highest during the commencement weeks and declined thereafter. Potential causes of the observed pattern may have been the new environment which is a challenge to many of the new and often cognitively impaired residents. They are non used to the bedroom, the way to the toilet or may have difficulties finding the light switch. These aspects may have been responsible for an increased run a risk of falling. Some other report in old community-dwelling people found that the first weeks later on discharge from hospital were associated with an increased risk for femoral fractures [three]. A morbidity-related weakness with a deterioration of gait and balance, and a withal (sub-acute) delirium may exist farther reasons for a transient increased risk of falling which could explain the observed time-dependent pattern. All the to a higher place mentioned intrinsic and extrinsic reasons for falls could exist also present when people are admitted to hospital or transferred to a rehabilitation clinic. Therefore, time-dependent fall risks may be as well found in hospitalised patients. This is of specific involvement in geriatric patients transferred to a rehabilitation clinic since their fall rates have been reported to be particular high [iv, 5]. In improver, rehabilitation may take contrary impacts on autumn rates. On the one mitt, exercise improves strength, residual and gait, on the other hand increasing concrete activity increases the time at risk. Finally, specific subgroups of patients being in rehabilitation may have completely different time-dependent patterns of fall risk. This could be of relevance for the initiation of subgroup-specific preventive measures.

Many studies reported fall rates in hospitalised patients [6–11]. A few of these studies suggested even higher fall rates during the kickoff days of hospitalisation [eight–10]. These studies, even so, did non analyse this topic systematically and did usually not consider changing person-days at risk due to discharge, transferral or decease. There are no studies and so far which analysed fall rates or risk factors for falls as a part of time after admission to an acute or sub-acute hospital in a systematic fashion.

In our report, we analysed a) fall rates as a function of time after admission to a geriatric rehabilitation dispensary and b) the time-dependent impact of different clinical baseline factors on fall risk in more than 5,200 hospitalised patients.

Methods

Setting and report population

The analyses were performed with an anonymized dataset which included all patients admitted to 1 geriatric rehabilitation dispensary in south-west Germany between one.01.2010 and 31.12.2014. Geriatric rehabilitation is usually preceded by a stay in an acute intendance hospital. Patients with femoral fracture, for example, are normally transferred to the geriatric rehabilitation clinic later 10 − 14 days of acute care. Frequent reasons for geriatric rehabilitation are fragility fractures such as hip fracture, neurological diseases such as stroke, lower limb amputation, or cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction or congestive center failure. The length of stay is usually 3 weeks merely tin be extended past 1, 2 or in rare cases even more weeks.

Baseline characteristics

All variables were retrospectively extracted from the electronic hospital information system. The Barthel-Index (BI) is a widely used, standardized tool for measuring functional status. Patients are scored in ten dissimilar activities of daily living (ADL) upon their independence of performance. The total score ranges from 0 (complete dependence) to 100 (complete independence) [12]. DemTect is a screening tool to place patients with mild cerebral impairment and dementia in the early on stages of the affliction. Information technology includes 5 tasks and its score ranges from 0 to 18 points [13].

The degree of orientation and the Barthel-Alphabetize were assessed and recorded past a nurse at the admission day. Cognition (DemTect) was assessed by an occupational therapist during the first calendar week of stay. For the analyses the variables were dichotomised (fully oriented vs. non fully oriented; strong cognitive impairment (DemTect 0–8 points) vs. slight or no cognitive impairment (DemTect ≥nine points); depression functional condition (BI <60) vs. ameliorate functional status (BI ≥60)). The cut-off point of the Barthel-Index was chosen according to the median value inside the study population.

Nosotros did not include other measures of single activities of daily living like transfer scales or gait speed since they were already represented by the Barthel-Alphabetize or could non be performed by a large per centum of patients at access due to substantial functional impairments.

Falls

Each fall at the geriatric rehabilitation clinic has to exist electronically recorded past nurses and confirmed by a physician. Information about the exact appointment and time of the fall is bachelor. For the analyses these recorded falls were extracted from the electronic infirmary information organisation.

Statistics

If a patient had two or more rehabilitation stays within the study period, each stay was handled independently. All falls of a patient were included in the dataset. Fourth dimension at fall risk at the day of admission and the twenty-four hour period of discharge is clearly less than 24 h and varies considerably between different patients due to organisational reasons. Therefore, the solar day of admission and the day of discharge were not included in the analyses. Only the actual time at autumn gamble was considered for the analyses. If a patient, for case, had to exist transferred to an acute ward at mean solar day 10, only the days 2–9 were used for the analyses. To analyse fall risk during rehabilitation as a function of fourth dimension after admission fourth dimension-intervals were divers. For the descriptive analyses 3-twenty-four hour period-intervals were chosen every bit a trade-off between temporal resolution and fall numbers. In improver, a subgroup assay was performed which was restricted to patients who got an extension of their stay beyond the usually granted rehabilitation menstruation of three weeks. The autumn rate was calculated by dividing the number of falls by the total number of person-days for each time-interval. The rates are presented every bit falls per one,000 person-days with 95 % confidence intervals. The rates represent the expected number of falls in 1,000 patients being at chance for 1 day in the respective time-interval.

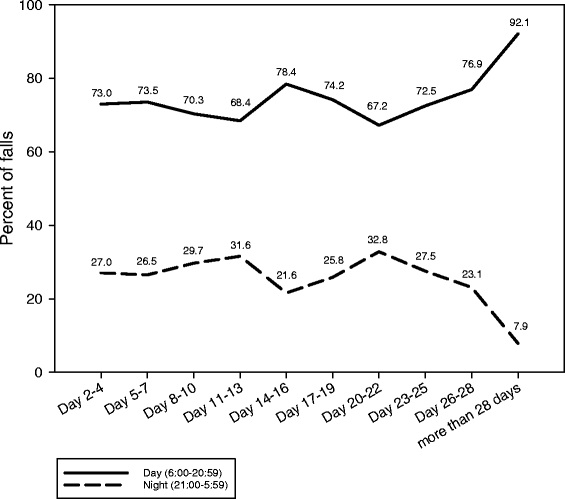

The pct of falls at 24-hour interval and night was calculated for the in a higher place divers fourth dimension-intervals. Time for day and night was chosen according to the time intervals in which the bulk of patients is either involved in daytime activities (6:00–xx:59) or stay in bed for night's rest (21:00–5:59).

To analyse if the influence of unlike covariates as risk factors for falls changes over time separate negative binomial regression models were applied for dissimilar time-intervals later admission. In order to reach a sufficient number of autumn events for the regression models, the period of a complete week was used for each of the first 4 fourth dimension intervals. The time catamenia beyond four weeks (>28 days) was treated every bit one time interval. The multivariate models included gender, age, diagnosis, functional status (BI) and orientation. Cognition (DemTect) was not included in the model since it is not assessed directly at admission and is non reliable in disoriented patients. Falls are correlated with future falls, and multiple falls of i person either in 2 rehabilitation stays or inside 1 rehabilitation stay are therefore not contained events. To account for this correlation of falls, a sensitivity analysis was performed. Only a patient's first rehabilitation stay and but his/her starting time fall were included. For each time-menstruum a Cox proportional hazard regression assay was performed which included the same variables than the negative binomial regression models. Time afterward the first autumn was censored.

Results

The dataset consisted of 5,255 patients hospitalized in a geriatric rehabilitation clinic. 12 % of the patients had 2 hospitalizations and 2.4 % of the patients had more than 2 hospitalizations. The patients' median historic period was 83.0 (interquartile range: 77.seven; 87.3) years, the median length of stay was 22 (interquartile range: twenty; 29) days. The nigh frequent reason for rehabilitation were femoral fractures (24.2 % of all patients) followed by stroke (9.7 %). One fourth of the patients was assessed as beingness disoriented at the time of access and about i third was observed as having potent cognitive impairment, which was assessed by a cerebral test during the outset week (DemTect 0–viii points). In total, 1,115 falls occurred within 109,457 person-days resulting in an overall autumn charge per unit of ten.two falls/1,000 person-days. During the 5,255 rehabilitation stays, 560 (10.7 %) patients had i fall, 129 (2.5 %) patients 2 falls and 75 (1.4 %) patients more ii falls.

The fall risk was non constant during the length of stay in the rehabilitation clinic. In all patients combined, the autumn rate was highest during the first week (13.3 falls/1,000 person-days) and decreased by virtually ane third within the second and third week (Fig. 1a). This pattern was more pronounced in men than in women (Fig. 1b). For femoral fractures the pattern of fall run a risk over time was comparable to that of all patients combined. Patients with stroke had a mostly higher fall take a chance than patients with femoral fracture but a less pronounced risk pattern over fourth dimension (Fig. 1c). Clearly higher fall risks were observed during the first week in disoriented patients, in patients with a depression functional status and in patients with strong cognitive harm during the first calendar week. Their fall gamble dropped by nigh one half during the following weeks. In disoriented patients, for example, the fall charge per unit decreased from 24.6 falls/1,000 person-days in day 2–four to about 13 falls/i,000 person-days two weeks later on. In dissimilarity, no consistent time-dependent pattern was observed in fully oriented patients, in patients with a better functional status and in patients without or but slight cognitive harm (Fig. 1d–f). The exact estimates are also presented in the Boosted file 1: Tables A-One thousand. Well-nigh of the above reported analyses showed an increase of the autumn rate subsequently the 3rd week. This is mainly due to a selection of frail patients who got an extension of their stay beyond the ordinarily granted rehabilitation period of 3 weeks. If this group of patients was analysed separately the observed increment of the fall rate later on the third week disappeared (Additional file one: Tabular array B).

Autumn rate as a role of fourth dimension (a) after admission to the rehabilitation clinic, (b) stratified past gender, (c) past diagnosis, (d) by orientation, (e) by Barthel index, (f) by cognitive function (DemTect)

Apart from the concluding time interval (>28 days), the distribution of falls betwixt solar day and night was relatively abiding over fourth dimension (Fig. 2).

Distribution of falls betwixt mean solar day and nighttime stratified by time after admission to the rehabilitation clinic

During the starting time calendar week (twenty-four hour period 2–vii) the variables male gender, low functional status (Barthel-Index <60) and being disoriented increased the chance of falls significantly (Table 1). In the post-obit weeks the relative risk for falls decreased considerably for being assessed as disoriented at access and gradually for low functional status at admission. In contrast, the take a chance of falls for patients with the diagnosis stroke increased during the final two time intervals with incidence rate ratios of ii.06 (95 % confidence interval 1.13; three.76) and two.24 (95 % confidence interval ane.ten; 4.58) (Table ane). The sensitivity analysis which considered only the first rehabilitation stay and the first autumn did non make a meaningful change of the results (Boosted file 1: Table H).

Discussion

Nosotros found fall rates to be a role of fourth dimension later on admission to a geriatric rehabilitation clinic. A particularly pronounced risk design with high autumn risks during the beginning days of sub-astute hospitalisation and decreasing risks thereafter were observed in subgroups of male patients, disoriented patients, patients with a low functional condition or impaired knowledge. Their fall risk inside the starting time days was at least double as high as in the corresponding patients without these characteristics or limitations and decreased to virtually one half during the following weeks. As a consequence, the incidence rate ratio of baseline characteristics changed over time. In contrast, the distribution of falls betwixt day and night seemed to be relatively constant during the rehabilitation menstruation.

The observed mean fall rates were higher than in medical astute intendance settings [6, 7, 14] merely in line with fall rates from acute and sub-astute geriatric units [four, 5, 15]. Rehabilitation is always a trade-off between run a risk-increasing mobilisation and safety. This may be one reason for the relatively loftier fall rates of patients treated in geriatric rehabilitation centres. Three studies mentioned already higher fall risks during the showtime days of a hospital stay [eight–10]. These studies, even so, have methodologic limitations and did not analyse our research question in detail.

The time-dependency of fall run a risk was especially pronounced in disoriented people and in people with low functional status (BI <60). Explanations for the observed take a chance reduction over fourth dimension in these two examples could exist a gradually better orientation in the new environment, a declining delirium during rehabilitation or benefits due to rehabilitative measures particular in subgroups with a high adventure of falls.

The identified risk factors of falls are identical to the results of a big torso of literature [11, 16]. Our analyses add to the literature in the style that they demonstrate that the patient'southward clinical characteristics assessed at baseline may modify over brusque fourth dimension periods and crave a continuous reappraisal of the patients' fall risks. This is probably one of several reasons why fall risk assessment tools take only limited examination properties [17].

Our information point that the fall take a chance was particularly a trouble of patient subgroups during the early days subsequently access to the rehabilitation clinic. Therefore, interventions which focus on patients with disorientation or low physical function within the first days after admission appear to be appropriate. Generally, a close supervision of loftier-run a risk patients during the high-risk period seems to be reasonable. Another measure could be prompted voiding in order to reduce fall take a chance on the fashion to the toilet. Sensor mats which give an alert if the patient gets out of bed may exist an pick particularly during night. Depression-low beds could be used in agitated patients to make getting up more than difficult and to reduce fall top. Hip protectors do not reduce fall run a risk simply may reduce the take a chance of hip fractures [18]. Despite the obvious intuitive value of all the mentioned measures in that location is no direct empirical testify for unmarried measures in preventing falls or fall-related injuries in hospital [xi]. Based on systematic reviews, the virtually appropriate approach to fall prevention in the hospital environment includes multifactorial interventions with multi-professional person input [xi, 19]. It is not clear if a gamble reduction can be achieved already within the first days after admission. A large successful intervention study in sub-acute wards observed an effect even not before a stay of 45 days [20]. Two recently published studies from Commonwealth of australia evaluated the effect of multifactorial fall prevention measures in acute and sub-acute intendance. The first report applied exactly the above suggested measures in the acute hospital setting but did not reduce the rate of falls [21]. The other study was performed in aged care rehabilitation units and demonstrated a reduction of falls and fall-related injuries [22]. This study, yet, used an individualised falls-prevention teaching programme for patients and may exist therefore merely of limited value in disoriented or cognitively impaired patients who have been shown in our report to exist of item chance during the starting time week. Our study does not tell which interventions will be finally successful. Even so, it shows clearly that futurity studies should focus on interventions which aim to influence the autumn take a chance particularly in specific patient subgroups particularly during the high-risk menses after admission.

Strengths of the study are the accurate documentation of falls and the exact consideration of fourth dimension at risk in each analysed time-interval. The large number of patients and falls immune evaluating fall rates fifty-fifty in small time periods. This study has also limitations to consider. First, but those falls were included in the analyses which were noticed by the staff. This results probably in an underestimation of the fall rate. Second, information technology cannot be completely excluded that the proportion of noticed and unnoticed falls inverse during rehabilitation due to unlike time spent on individual care over fourth dimension by the nurses. Third, the setting of a geriatric rehabilitation clinic is specific and its instance mix and its daily routine differs from astute intendance settings, from organ-specific rehabilitative settings and fifty-fifty from geriatric settings of other countries. Therefore, the generalizability of the results has limitations.

Conclusion

In summary, we institute the fall gamble during rehabilitation to be time-dependent. The strongest clan betwixt time and fall risk was observed in functionally express patients with high risks during the starting time days after access and declining risks thereafter. A substantial reduction of falls can be but expected if future fall prevention measures influence the fall take a chance in these subgroups specially during the high-risk catamenia after access.

References

-

Rapp K, Lamb SE, Klenk J, Kleiner A, Heinrich S, König H-H, et al. Fractures after nursing home admission: incidence and potential consequences. Osteoporos Int. 2009;xx(10):1775–83.

-

Rapp One thousand, Becker C, Lamb SE, Icks A, Klenk J. Hip fractures in institutionalized elderly people: incidence rates and excess bloodshed. J Os Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(eleven):1825–31.

-

Rapp Thousand, Cameron ID, Becker C, Kleiner A, Eckardt M, König H-H, et al. Femoral fracture rates after discharge from the hospital to the community. J Os Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(4):821–7.

-

von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. Incidence of in-hospital falls in geriatric patients before and afterward the introduction of an interdisciplinary team-based fall-prevention intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):2068–74.

-

Schwendimann R, Bühler H, De Geest S, Milisen Chiliad. Characteristics of hospital inpatient falls beyond clinical departments. Gerontology. 2008;54(6):342–8.

-

Healey F, Scobie S, Oliver D, Pryce A, Thomson R, Glampson B. Falls in English and Welsh hospitals: a national observational study based on retrospective analysis of 12 months of patient safety incident reports. Qual Saf Wellness Intendance. 2008;17(6):424–30.

-

Bouldin ELD, Andresen EM, Dunton NE, Simon One thousand, Waters TM, Liu G, et al. Falls among adult patients hospitalized in the United States: prevalence and trends. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(1):xiii–7.

-

von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. When do elderly in-infirmary patients fall? Age Ageing. 2004;33(four):413.

-

Vassallo Thou, Sharma JC, Briggs RSJ, Allen SC. Characteristics of early fallers on elderly patient rehabilitation wards. Age Ageing. 2003;32(3):338–42.

-

Schwendimann R. Frequency and circumstances of falls in acute care hospitals: a pilot study. Pflege. 1998;11(half-dozen):335–41.

-

Oliver D, Healey F, Haines TP. Preventing falls and autumn-related injuries in hospitals. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(4):645–92.

-

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Physician State Med J. 1965;fourteen:61–5.

-

Kalbe E, Kessler J, Calabrese P, Smith R, Passmore AP, Make Grand, et al. DemTect: a new, sensitive cognitive screening test to support the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and early dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;nineteen(2):136–43.

-

Heinze C, Halfens RJ, Dassen T. Falls in German in-patients and residents over 65 years of age. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(three):495–501.

-

Nyberg L, Gustafson Y, Janson A, Sandman PO, Eriksson South. Incidence of falls in iii different types of geriatric care. A Swedish prospective study. Scand J Soc Med. 1997;25(ane):8–xiii.

-

Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Take a chance factors for falls in community-domicile older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2010;21(5):658–68.

-

Oliver D, Healy F. Falls risk prediction tools for hospital inpatients: do they piece of work? Nurs Times. 2009;105(vii):eighteen–21.

-

Parker MJ, Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ. Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;iv:CD001255. Review.

-

Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Murray GR, Hill KD, Cumming RG, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD005465.

-

Haines TP, Bennell KL, Osborne RH, Hill KD. Effectiveness of targeted falls prevention programme in subacute hospital setting: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328(7441):676.

-

Barker AL, Morello RT, Wolfe R, Brand CA, Haines TP, Hill KD, et al. 6-PACK programme to decrease autumn injuries in acute hospitals: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2016;352:h6781.

-

Hill A-Grand, McPhail SM, Waldron N, Etherton-Beer C, Ingram K, Flicker L, et al. Fall rates in hospital rehabilitation units after individualised patient and staff instruction programmes: a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;385(9987):2592–nine.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

There were no sources of funding for the enquiry reported.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed during the current study is bachelor from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors'contributions

KR: Analysis and interpretation of data, training of manuscript. JR: Assay and interpretation of data, revision of manuscript. UL: Estimation of data, revision of manuscript. CB: Interpretation of data, revision of manuscript. AJ: Analysis of information, revision of manuscript. JK: Analysis and estimation of data, revision of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

None of the authors has whatsoever financial interest, patents, company holdings, or stock to disclose related to this project.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ideals approval and consent to participate

The written report was canonical by the ethical committee of the Academy of Tübingen (projection number 241/2016BO1). The need for consent to participate was waived by the Ideals approval. Permission to analyse the patients' data was obtained from the hospital the information were derived from.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional file

Additional file ane:

Table A: Fall charge per unit equally a function of fourth dimension after admission to the rehabilitation clinic (all patients combined). Table B: Fall charge per unit as a function of time subsequently admission to the rehabilitation dispensary in patients with a length of stay of more than 22 days (all patients combined). Table C: Fall charge per unit as a part of fourth dimension after access to the rehabilitation dispensary stratified by gender. Table D: Fall rate equally a function of fourth dimension after admission to the rehabilitation clinic in patients with a femoral fracture or stroke. Tabular array E: Fall rate as a function of fourth dimension after admission to the rehabilitation clinic stratified by the caste of independence in the activities of daily living (Barthel Index). Tabular array F: Fall rate as a role of time after admission to the rehabilitation clinic stratified by the degree of orientation. Tabular array K: Autumn charge per unit equally a office of time subsequently access to the rehabilitation clinic stratified by cognitive function (DemTect). Table H: Influence of gender, age, diagnosis and role at baseline on fall rate stratified past different time intervals later admission to the rehabilitation clinic (sensitivity assay). (DOCX 38 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and betoken if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/naught/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rapp, G., Ravindren, J., Becker, C. et al. Fall risk as a part of time after access to sub-acute geriatric infirmary units. BMC Geriatr sixteen, 173 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0346-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0346-7

Keywords

- Adventitious Falls

- Rehabilitation Centers

- Confusion

- Femoral Fractures

- Stroke

Source: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-016-0346-7

0 Response to "Functional Measures for Fall Risk in the Acute Care Setting a Review"

Post a Comment